Geoffrey Winthrop Young was a celebrated mountaineer and rock climber, as well as a poet, author and educator. He was injured in the First World War, which resulted in one of his legs being amputated.

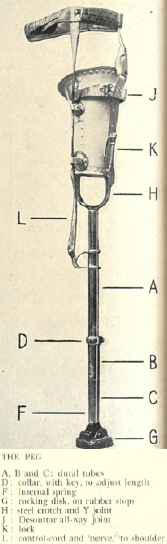

To enable him to continue climbing, Geoffrey designed an adaptable prosthetic leg, which had a number of detachable feet for scaling different types of rock and snow – ‘a leather shoe device, a rubber pad, a ski-ring fitment to stop the leg plunging into snow, and for rock climbing a steel spike, studded with nails, that he could ram into nicks and crannies’ (Hankinson 1995).

In a letter he wrote to his friend George Mallory in 1917, he described his experiences of climbing after his injury as ‘the immense stimulus of a new start, with every little inch of progress a joy instead of a commonplace’ (Ibid).

Geoffrey Winthrop Young’s adaptable prosthetic leg, which he called ‘The Peg’

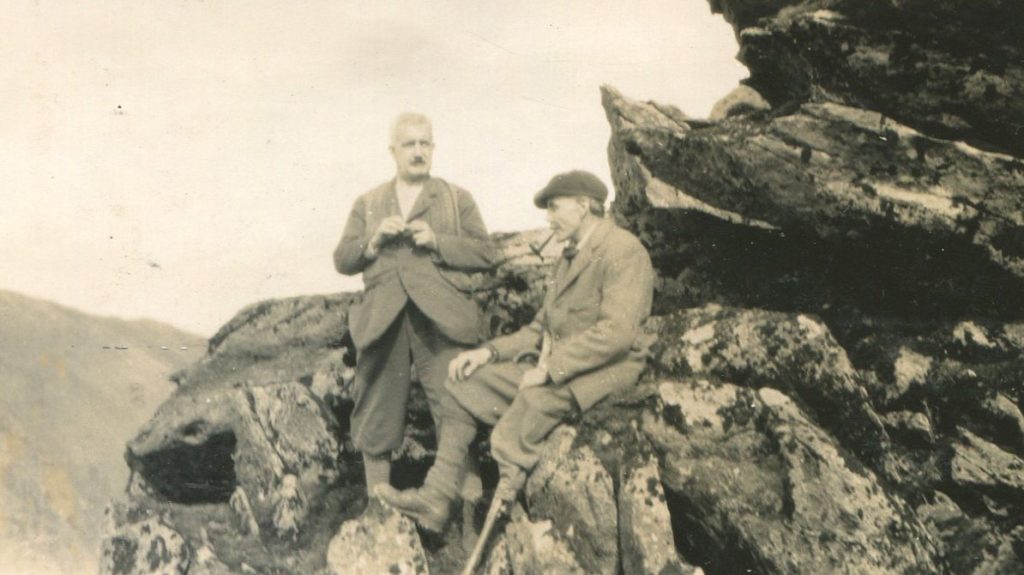

Geoffrey Winthrop Young climbing on a crag in North Wales, early 1930s. From Richard Hargreaves’ collection

Geoffrey was described by many as a man with intuitive sympathy; he encouraged others who had returned from war with injuries to continue the activities they loved.

Geoffrey Winthrop Young and HE Scott on Snowdon Summit, 1926. By kind permission of Fell and Rock Climbing Club Archives of the English Lake District

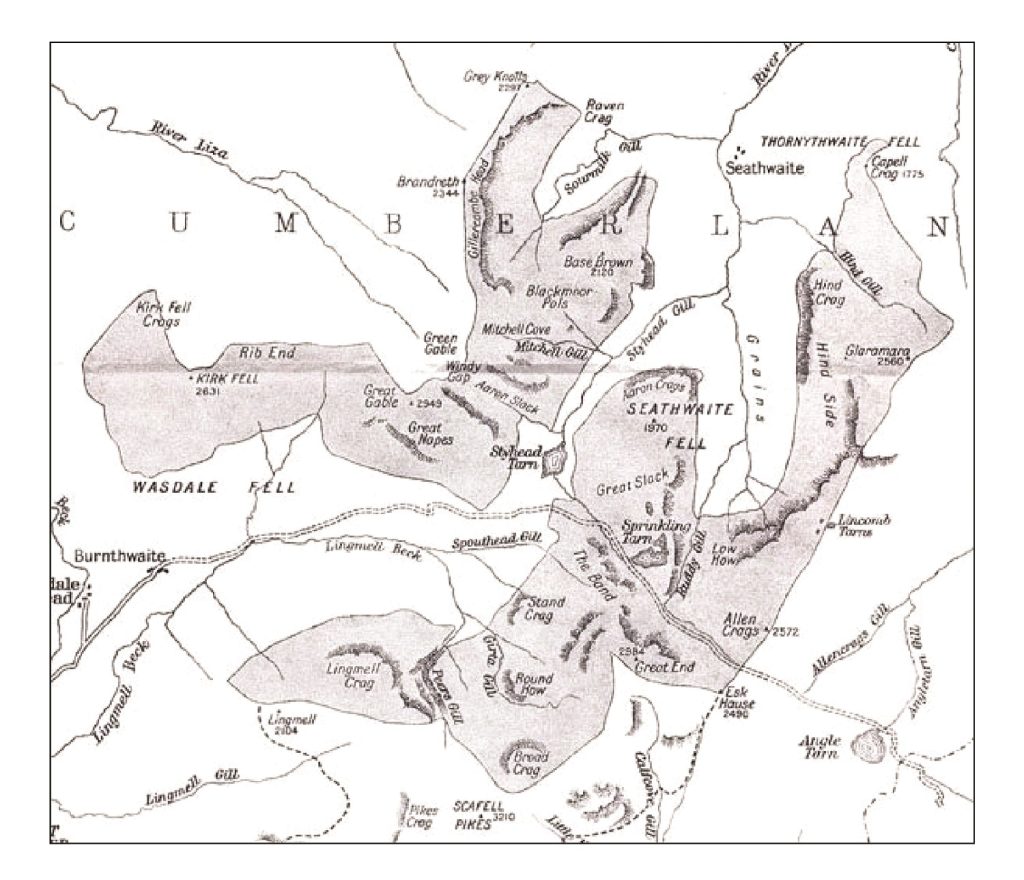

In 1923, the Fell and Rock Climbing Club gifted 12 mountain summits in the Lake District, including the Great Gable, to the National Trust as a war memorial. Geoffrey was invited to write and deliver a dedication speech at the unveiling ceremony on the Gable’s summit. It was the longest and toughest climb Geoffrey had tackled since before the war. Over 500 people listened to his tribute in the rain, wind and mist at the top of the summit.

Map of 12 mountain summits in the Lake District. By kind permission of Fell and Rock Climbing Club Archives of the English Lake District

At the time, it was the largest gift of land that had ever been made to the National Trust and it proved a significant turning point in the history of land preservation in England.

The song Fellowship of Hill and Wind and Sunshine that features in the Everywhere and Nowhere film, was a new musical arrangement of Geoffrey Winthrop Young’s dedication speech by Dr Dave Camlin, performed and recorded on the summit of Great Gable in 2018. To hear the song in full visit here.

This was created in the centenary year of the end of the Great War. The National Trust commemorated the gift of 12 summits in the Lake District to the nation as a war memorial. As part of these commemorations, a special song cycle was performed and recorded on the top of Great Gable and the other fells gifted to the nation by the Fell and Rock Climbing Club.

Alternative reading

We invited people with lived experience of disability to offer their own personal reflections on some of the stories in Everywhere and Nowhere. In the section below sculptor and disability rights activist Tony Heaton offers an alternative reading of Geoffrey Winthrop Young’s story.

Initially it was the triumph over adversity element of Geoffrey’s story that resonated with me, but this can be tricky ground, as stories like this can be presented in a very ableist way. They are often described within the politics of disability as ‘tragic/brave’ or ‘show us yer stumps’ – where non-disabled people are in awe of disabled people and not understanding disability as an ordinary aspect of human life. Instead seeing disability as a difficult to comprehend phenomenon, and when presented as such will often alienate disabled people who perceive themselves to be portrayed as in some way ‘othered’.

It resonated because when I became a wheelchair-user back in 1970, NHS issued wheelchairs were heavy, unwieldy, and designed to push disabled people around in, whereas young people like me wanted to not only self-propel but we wanted lightweight, customised ‘chairs, fast, and made-to-measure, we wanted to get about independently and play sport such as wheelchair basketball. Consequently, we began to hack the NHS standard ‘chairs or build from scratch the ‘chairs we wanted, as opposed to the ones we were issued that we considered not fit for purpose. Just as Geoffrey set about customising prosthetics that met his climbing requirements.

The parallels with Geoffrey’s story are the idea that, like him, following impairment we wanted to return to enjoying our passions in life, we wanted autonomy, not ‘care and control’ which was often imposed on us by the drip, drip, drip of ‘you can’t do that anymore’ the casual ableism that had written us off, we were taking control, just as he wanted to do when looking for practical solutions to enable him to resume climbing and a life outdoors.

I thought this comment Geoffrey made was a critical insight: ‘the immense stimulus of a new start, with every little inch of progress a joy instead of a commonplace’, when describing his experiences of climbing after his injury. The idea of making a new start and being encouraged to do so, developing a positive approach to problem-solving and lateral thinking. This is where progress needs to be continually made.

Reference:

Hankinson, A. (1995) Geoffrey Winthrop Young: Poet, Educator, Mountaineer. London: Hodder & Stoughton